It’s early March, 2023. Our auction gallery is all set up for preview. Paintings are hung neatly on the slatwall, and shelves are full of interesting historic items. We’re all ready for the following weekend, when our semi-annual themed auction we call “The American Sale” will commence. The door chimes, and the front desk buzzes in a group of five well-dressed individuals.

“Welcome to Blackwell Auctions! What can I do for you?”

They hesitate, then one of them says quietly, “We’d like to see the watch.”

“Sure thing – be right back,” I tell them, then walk to the back to one of the safes to get it.

I’ll admit that at this point, I’m pretty excited. Some buyer is so serious about this piece, a team of experts has been sent here to examine this national treasure. I set the watch carefully onto a velvet-lined jewelry tray and walk back to the group standing in the lobby.

“Would y’all like to sit at the conference table to look it over?” I ask.

One of them reaches into a jacket pocket and pulls out a document. The rest of them smoothly hold up badges.

“We’re Special Agents with the National Parks Service,” one of them declares, then gestures to others in his group, “and the Federal Bureau of Investigation.” He hands me the document. “And this is a federal warrant authorizing the seizure of this watch and of all materials you have that are associated with it.”

Months earlier …

I was looking at dozens of watches and jewelry strewn over my client’s desk. A retired jewelry dealer and watch collector from up north, my client had consigned a number of items with us, and we’d built a good working relationship. In one of the shoeboxes stuffed with small manila envelopes (each one containing a wristwatch or pocket watch), I noticed that one was wrapped carefully with a cloth.

“What’s that one?” I asked. Because I’m nosy. It’s a nosy business.

“Oh, that one might be special,” he replied, and unwrapped a nondescript silver pocket watch. The watch case was plain, with no engraving. It was worn.

I thought, that’s worth a hundred dollar bill if it’s running. But he knew what I was thinking. “Open it,” he said.

I pressed the top, and the lid popped open. Plain vanilla white face. American Waltham, coin silver case. Yep, it’s worth about a hundred bucks. And then I looked at the inside of the lid.

THEODORE ROOSEVELT, from D.R. & C.R.R.

I immediately recognized how potentially important this watch could be. This was not a watch presented BY Theodore Roosevelt. It was a watch given TO Theodore Roosevelt.

But it’s not only a nosy business. It’s also a skeptical business. I’ve seen hundreds – if not thousands – of reproduction (or downright fake) items: watches, coins, sports cards, autographs, art, jewelry. Name pretty much anything of significant value, and I guarantee someone’s faked it at some point. I examined the watch with my loupe and uttered a “hmm” or two.

“Any idea on the initials?” I asked.

“I looked that up, and I think maybe D.R. and C.R.R. were his brother-in-law and sister,” my client answered. “Roosevelt’s sister’s name was Corinna, Corinne or something like that.”

“I mean, if this is real, what a find,” I told him with deft mastery of the obvious. “How the heck did you get this?”

My client told me the whole story: He ran a jewelry business in New York in the late 1980s, and a local picker with whom he’d become friends would borrow small sums of money from him for working capital. He’d leave the watch in my client’s possession until he returned what he borrowed, usually within a week or two. This went on for some years. Finally, after lending the picker some money and not hearing from him for a while, my client called his number. The man’s wife answered, saying that he’d passed away suddenly, so whatever my client had as collateral was now his.

“So you’ve had this for, what, 35 years?” I asked.

“About that, 30 or 35 years,” he replied. “I don’t even know if it’s real or not. I’ve always figured it wasn’t.” I turned it over in my hand several times.

“I’d love to research this, and if I find out that it’s right, I’ll sell it for you,” I said.

He chuckled, took the watch and wrapped it back up, then set it on his desk. We talked a little more about the other things he was giving me to sell.

On a visit to his home several months later — after I’d forgotten all about the watch, actually — he pulled it out and handed it to me.

“I’ve never done any real research on this. Find out what you can, and we’ll talk.”

Due diligence

Research often goes way beyond a Google search. Sometimes it’s tempting to believe you have an answer, when all you really have is a search result.

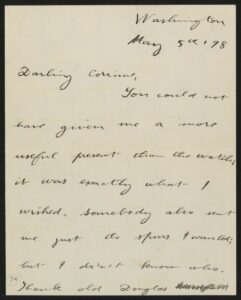

My first task was to match the initials with members of Roosevelt’s family. That took only a simple Google search. Douglas Robinson was indeed his brother-in-law, and Corinne Roosevelt Robinson, his sister. Thus D.R. and C.R.R.

Next, I searched for the watch itself. No photos that I could find online. No mention of the watch anywhere. A hundred searches all turned up nothing. But I did come across some mention of how prolific of a letter-writer Roosevelt was, and that many of his letters were addressed to his sister, Corinne – about 400 total, I discovered.

But here’s the thing: Most of his letters online – thousands of them – are just images of his letters, not searchable text. Deciphering semi-legible cursive is tiring. But, I thought, maybe one of them holds a clue. So I started reading them. Then, after finding one particular letter which he wrote to Corinne while in San Antonio, about to travel to Cuba, I decided I needed to read them all, which I’m pretty sure I did.

The letter began, Darling Corinne, You could not have given me a more useful present than the watch; it was exactly what I wished … Thank old Douglas for the watch – and for his many, many kindnesses.

“The game’s afoot,” I remember thinking. I might even have said it out loud.

For the next few weeks, I was consumed with researching the watch. I wrote to numerous organizations and museums related to Theodore Roosevelt, trying to find out anything I could about the possible authenticity of the watch.

My client was excited when I shared the text of the letter I found, but I told him we’d only a tiny fraction of proof – this was nothing more than a single pillar, not a whole foundation. We were a long way from proving anything.

Consulting the experts

At one point, I contacted an appraiser – a very well-respected specialist in the field of Americana – and described the watch to him. I offered to ship it to him and pay for him to examine it to determine its authenticity.

“Save your money,” he advised. “It’s a fake.” He proceeded to explain what I already knew: how clever forgeries can be, and how the greater the potential value, the better the forgery looks. All true, by the way. But I was a little surprised that he wasn’t the least bit curious about just handling it before rendering a verdict.

I talked with several colleagues who’d been in the antiques or watch business for decades. All of them told me it must be a forgery. Every last one of them gave it a thumbs-down. No way Theodore Roosevelt’s pocket watch could have found its way to Southwest Florida. No way that’s not in a museum. And, too, how did did it end up at Blackwell and not a major gallery, such as Sotheby’s, Christie’s or Heritage?

Back to the research

To be candid, after talking with so many people whose opinions I respect deeply, I was a little discouraged. So naturally I kept digging.

But I wasn’t trying to prove its authenticity.

In C.S. Lewis’ novel, The Pilgrim’s Regress, the personified character, Reason, says the following: “They pretend that their researches lead to that doctrine, but in fact they assume that doctrine first and interpret their researches by it.” (I’ve highlighted that whole passage and dog-eared that page.)

When I’m trying to determine an item’s authenticity, I don’t start with the idea that something is real, then interpret my research to prove it. Instead, I presume the worst. I play the prosecution, not the defense. If something seems too good to be true, it probably isn’t true. So I play the odds. I focus on trying to prove something is fake. If I fail to establish doubt, then I am left with something of an inevitability: It’s real. (I’m not saying this is the right way to establish authenticity — the Sherlock Holmes “once you eliminate the impossible” method — It’s just how I go about the process.)

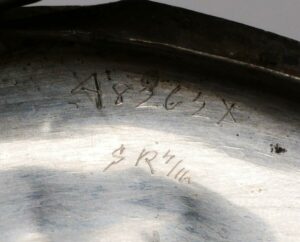

I checked the watch’s serial number. Did its manufacturing date allow that Corinne could have given it to Roosevelt in 1898? Or was it made in 1899 or 1900? Nope, the date was right.

I spent time looking at service marks inside the case. These are almost microscopic marks made by jewelers who service or clean watches. Often they are encoded, and therefore somewhat worthless. But sometimes they’re just dates. And I found one tiny mark, “S.R. 4/16,” that appeared to indicate a repair date of April 1916 by someone with the initials “S.R.” That took me on a quest to find out what Roosevelt might have been doing not long before that, something that might have affected the functioning of his watch. (My fruitless digging through online business directories for a watch repair shop operating around 1914 in New York, with an employee named S.R., took me a couple of hours, as I recall.)

Hours of reading later, I came across a paragraph from his 1914 book, Through the Brazilian Wilderness. In it, the former president writes about a particularly difficult bayou crossing: One result of the swim, by the way, was that my watch, a veteran of Cuba and Africa, came to an indignant halt.

The service mark represented a date two years after he came back from Brazil. But Roosevelt nearly died during that expedition, and he was never the same, health-wise, after he returned to New York. It makes sense that having his watch fixed wasn’t high on his priority list.

All of that still added up to conjecture. But it all added up.

Everything was right about the watch. The name and initials on the inside were hand-engraved, not rolled or stamped, and the lettering was smooth – any sharpness to the lettering might indicate that it was done more recently than 125 years ago. The serial number range was right. The service number seemed to fit. The patina and wear were typical. The background story – who gave Roosevelt the watch – was all documented. Even the fact that it was a Waltham made sense, as Roosevelt seemed to favor Walthams. At least a couple of pocket watches he gave as gifts were made by Waltham.

So after weeks of research, discouragements and eureka moments, I went back to my consignor with this message: I believe it’s right. That this was Roosevelt’s watch. But short of a photo of him with it – which doesn’t exist – or a more thorough back story, there’s no way we can prove it definitively.

But he let me offer it anyway. After all, I’d already alerted dozens of people associated with museums and Roosevelt organizations, including Sagamore Hill. I’d advertised it in print and online, and run press releases about the auction, highlighting the watch.

Now it was up to the bidders. Would they believe the evidence I’d gathered? Was it enough?

Savvy buyers almost always demand provenance. And just about all I had was my own firm belief – based on a lot of evidence – a belief shared by pretty much nobody else in my orbit.

Fast forward

“And we’re serving a federal warrant authorizing the seizure of this watch and of all materials associated with it.”

Well, that is not what I expected. I stand there for a second or two with what had to be a blank expression. A couple of my staff are behind the front counter, silent and stunned. The only noise in the room is the soft whoosh of the air conditioning.

I make it a point not to get creative with law enforcement (and my parents raised me to respect them), so I take the warrant and hand the tray to one of the agents, who takes hold of it very gently.

“We’d like to ask you a few questions, too, if you have time,” one says, “and if you can gather all the materials you have – all of it – we’d like to have that, too.”

We go sit at the conference table in the auditorium, and they begin asking me about the watch, what I’d discovered, how I’d discovered it, who my consignor was, how he came by the watch, and so on. Some of their questions are restatements of previous questions. I’m sure they want to see if my story changes at any point.

A few minutes into the interview, I suddenly understand the real significance of this unexpected scene. I reach both hands up to cover the sides of my face. To push my cheeks down. I suppose what I’m doing is obvious, so I move my hands away from my face and cross my arms on the table.

“Are you okay, Mr. Bailey?” the lead agent asks.

I smile. I start laughing a little, then a little more. My eyes start tearing up. I’m sure I looked like a lunatic. One FBI agent is on the other side of the gallery photographing every page of research I had – our consignment forms, copies of correspondence – and there are four federal agents at my conference table. I’m effectively being interrogated. And I’m downright giddy.

“Mr. Bailey,” the agent prompts again.

“I was right!” I blurt out, punctuating each syllable with a chopping motion. “Nobody I talked with – I mean nobody – believed this watch was Roosevelt’s. But I knew I was right!” The ice breaks. The agents all smile.

The lead agent sets the watch down onto the velvet and leans forward.

“Can you see my hands shaking?” she asks. “Yeah, you were right. This was Roosevelt’s pocket watch.”

In 1987, the National Parks Department lent the watch to the Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural Site in Buffalo, N.Y. Apparently, the watch was kept in an unlocked display cabinet, and someone decided to take it with them. The identity of the thief remains unknown, at least publicly (in case you’re wondering, my consignor was never a suspect).

All of Blackwell’s research, promotion and advertising apparently caught the attention of a long-retired board member from one of the organizations we’d reached out to. He remembered something about how a Roosevelt watch was stolen out of an unlocked case in a museum decades ago. And that’s when the organization called in the feds.

(Somehow the story got modified into “the auctioneer decided not to offer it, and instead he contacted the FBI.” But I did no such thing. Had I known the watch was stolen, I never would have advertised it for sale in the first place. I never would have contacted multiple organizations about it, except for the museum that had it last.)

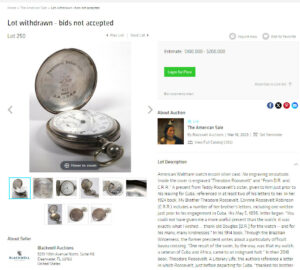

Anyway, Blackwell pulled the watch from all of our auction platforms, changing the title to a simple “Lot Withdrawn, bids not accepted.” The lead agent asked me politely not to go public with the story. Their investigation might be compromised if I did a press release about it. Sure, I could share the story among close associates. But I was asked not to make any public statements.

For 15 months, all we’ve done is whisper the story to people close to us.

A few days ago, I received a phone call from the lead agent with whom I’ve corresponded a few times. In a small ceremony, the watch was returned to Sagamore Hill. I could finally share all of this.

Yes, I know, it’s not like I found the ark of the covenant. It was a pocket watch. It wasn’t financially rewarding in any way, shape or form. It represented quite literally hundreds of hours of unpaid work.

But I got to play a role – however peripheral – in the recovery of a national treasure. I had the privilege of handling and researching arguably the most valued personal item carried by one of the four guys on Mount Rushmore.

I don’t feel any pride. I did nothing heroic. I just cooperated with feds who showed up with a warrant. I take credit for nothing but the thoroughness of my research, which led to the firm conviction that I was right about the watch. And that’s enough for me.

— Edwin Bailey

Afterword: I hope I made clear in the story that the NPS and FBI agents – particularly the NPS special agent with whom I’ve corresponded over the last year – were very courteous and professional. This was not some heavy-handed, dramatic, pre-dawn raid of Blackwell Auctions. We never felt pressured or threatened. Over the last several months, the lead NPS agent was always reachable, and she never came across as impatient with me (though I’m sure she must have been). Fact is, they could have made this experience an unpleasant one, and they didn’t.