As a piece of furniture, the cabinet is admittedly unremarkable: clean, Art Deco lines, with contrasting inlay and burl woods. The circular lock plate and hinges add to its sleek, industrial elegance. Open the doors, though, and everything changes. Some emotional response is almost inevitable.

As a piece of furniture, the cabinet is admittedly unremarkable: clean, Art Deco lines, with contrasting inlay and burl woods. The circular lock plate and hinges add to its sleek, industrial elegance. Open the doors, though, and everything changes. Some emotional response is almost inevitable.

On the back side of the left door is inlaid a cross. It’s not a religious symbol, but a cross with arms that flare out from a narrow center, and angled cuts at the end of each arm that create a star-like effect. On the right door, set into a field of burl, is an eagle in flight, grasping in its talons what has become one of the most universally reviled symbols in modern history: a swastika.

Like most people in my line of work, I run house calls, visit with walk-in consignors, and answer email inquiries. Most of my decisions about consignments are fairly straightforward and uncomplicated. The primary factors are price points, the kind of items we deal in, and, frankly, whether or not we feel we can work well with the prospective consignors. My job is to evaluate the value of an item – not just in monetary terms, but within its broader historical context. In some cases, that context involves pieces deeply intertwined with difficult or painful chapters of history. There is no simplicity when it comes to handling objects like this.

Yet, in my opinion, to ignore or dismiss them would be to deny their place in history. Artifacts such as this cabinet shouldn’t remain hidden away because they make us uncomfortable. They’re powerful, perhaps painful reminders of where we’ve been and where we mustn’t go again.

A very important nuance that is largely overlooked in emotional discussions on the subject is this: Many (probably most) WWII German artifacts were brought to the U.S. as war trophies: symbols of victory over Fascism, not the glorification of it. Perhaps one of the reasons a soldier from the Greatest Generation kept a war trophy was to remind him of how much it cost to acquire it.

As such, I feel that items such as this should be handled with respect. They’re not simply commodities to be sold, but also artifacts with important stories to tell.

What is it?

Now on to the cabinet itself: It measures about 32” high, 35” wide and 16” deep. A family of passionate antiques collectors in Pennsylvania purchased it in the 1960s. One of them was especially interested in militaria, and, over the course of five decades or so, he amassed an impressive collection of edged weapons, helmets, equipment and medals from the Civil War through the Vietnam War, with something of a focus on WWI and WWII. The family moved to Florida some years later, and the militaria enthusiast brought his collection with him, where it remained – in boxes piled six feet high throughout a two-bedroom condo in Pinellas County – until his recent passing.

On a side note, the consignor – one of the heirs – told me, when I first looked it over, that her family always said that this cabinet was made for Hermann Goering. Always the skeptic who believes that a family’s undocumented oral history is about as reliable as a very long game of Telephone, I recall wincing a bit and letting her know that – absent a photo of Goering standing next to it in his country home at Carinhall – the odds against that were astronomical. Because, well, they are. But I took it in, along with the rest of the collection, and started my research on it.

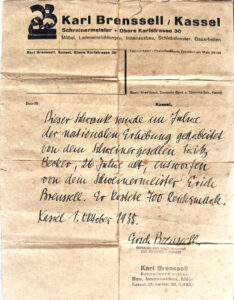

Accompanying the cabinet is a letter, written (in German) in late 1935. It states simply: “This cabinet was made in honor of the National Uprising by the journeyman carpenter Fritz Becker, 26 years old, and designed by master carpenter Erich Brenssell. It cost 700 reichsmarks.” The letter is signed by the owner of the Kassel-based company, Karl Brenssell, under whose name is printed “Mitglied der Reichskammer der bildenden Kunste,” indicating that he was a member of the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts.

Accompanying the cabinet is a letter, written (in German) in late 1935. It states simply: “This cabinet was made in honor of the National Uprising by the journeyman carpenter Fritz Becker, 26 years old, and designed by master carpenter Erich Brenssell. It cost 700 reichsmarks.” The letter is signed by the owner of the Kassel-based company, Karl Brenssell, under whose name is printed “Mitglied der Reichskammer der bildenden Kunste,” indicating that he was a member of the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts.

The letter reveals a few interesting facts. First, the cabinet was built in 1935, which is the same year the Luftwaffe was officially formed. Second, it was built in Kassel, Germany, where the aircraft and tank manufacturer Henschel (not to be confused with the more prominent Heinkel) was headquartered. And third, it cost 700 reichsmarks, a princely sum in 1935, given the fact that the average monthly wage for a skilled worker at that time was 100-150 reichsmarks. By some estimates, factoring in rates of inflation and buying power, 700 reichsmarks in 2025 U.S. dollars could have amounted to somewhere between $5,000 and $15,000. In any case, this piece was not commissioned by some newly promoted oberleutnant bomber pilot.

One interesting discovery about the piece itself is that the inside left and bottom cove molding trim pieces are simply set into place – they’re not nailed or glued – and when they’re removed, the entire inside structure can be pulled out, revealing hidden compartments along the top and sides. While false walls and secret drawers are fairly common features in antique furniture, it was still exciting to discover it. (The hiding spots were, unfortunately, empty.)

I was just about resigned to the conclusion that there were dozens of high-ranking Luftwaffe officers who might have wanted the swagger of owning such a cabinet – and that there was no real possibility of narrowing that field at all.

I’d pored over hundreds, if not thousands, of online images of Luftwaffe officers in various interior settings, hoping to catch a glimpse of this cabinet somewhere in the background. (Anyone who accessed my March 2025 Google search history would definitely get the wrong idea about my personal interests.) To be candid, I’d hit something of a wall.

Then in early April, I ran into an old friend of mine – an antiques buyer who’s something of a walking encyclopedia of WWII militaria. I hadn’t seen him since I brought the cabinet to the gallery. The first photo I showed him was of the left door (the one with the cross), and he immediately whistled, “Ooh, a Blue Max.”

And just like that, I had another rabbit hole to explore. To be candid, I’d ignored the cross entirely up until then, assuming it was a stylized Iron Cross, and focused mainly on the Luftwaffe emblem. But my friend identified the cross inlaid into the left door as a representation of the Pour le Merite, a WWI military award often referred to as the Blue Max – the most prestigious medal Germany awarded for extraordinary heroism. This award was discontinued in 1918, and its unique cross form wasn’t used for a military decoration again until 1939, four years after the cabinet was built.

Here’s where it got interesting. (And again, this is still something I’m investigating.) Using AI – and asking over and over in different ways, because I really don’t trust simple AI inquiries – I searched the list of Pour le Merite recipients from WWI and cross-referenced it against senior officers involved in the Luftwaffe as early as 1935. There were only four matches: Hans-Jürgen Stumpff, Eduard Ritter von Schleich, Ernst Udet and – you guessed it – Hermann Goering. Based on what research I’ve managed to do on these possibilities, I’ve all but ruled out Stumpff and von Schleich. They were evidently not politically active in 1935, and neither one seems likely to have commissioned such an expensive statement piece of furniture. Stumpff held the rank of lieutenant colonel in 1935, and von Schleich was a major at that time. 700 reichsmarks would have represented a couple of months’ pay for either man in 1935.

Ernst Udet, on the other hand, had both the means and the personality for such a piece. A fighter ace in WWI with a staggering 62 aerial victories, Udet was one of Germany’s top pilots, fighting in an elite unit under the command of Manfred von Richthofen, the “Red Baron.” He had accumulated some money and popularity during the 1920s-30s, and was well known for his profligate spending habits. In 1934, Udet became a key figure in the Luftwaffe, where he remained until taking his own life in 1941.

And Hermann Goering … well, everyone knows who he was.

Perhaps the collector’s family played a careful game of Telephone after all.

I’m a long way from claiming that this cabinet belonged to Goering or Udet. Without photographic evidence, some collectors will view the facts presented here as little more than compelling speculation.

But it is compelling.

Research – and an open mind – will continue right up to when we present all the facts and offer the cabinet to the buying public in our June 28 Militaria auction, “Pro Patria: Relics & Trophies of War.”

###

Additional note: There were two other field officers involved in the Luftwaffe in 1935 who were awarded the Pour le Merite in WWI – Robert Ritter von Greim and Theo Osterkamp. But given their comparatively modest status in the Luftwaffe in 1935, it seems highly unlikely (though not impossible) that either of them would have ponied up several months’ pay for a cabinet.